This horror game doesn’t simply employ trauma as atmospheric texture, but engages with the mental architecture of suffering

Samuel wants to move house. His belongings sit half-boxed in the hallway of his childhood home, the furniture covered in the minor chaos of transition. And yet, as you discover via a sequence of looping, Groundhog Day mornings, this is not a house he is either ready, or able, to leave. Either the house or Samuel’s subconscious resists every attempt at escape. Any place that lodges so immovably in the mind and body is usually either a site of joyous novelty or of unimaginable pain.

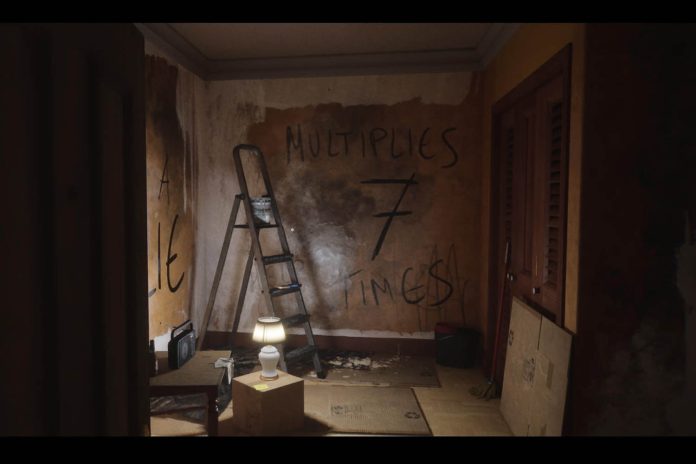

Luto is dark, melancholic and emotionally unsettling; it’s clear which kind of memories haunt this building. This isn’t horror constructed just from spider webs and jump scares – though there are a few, and they’re well- deployed and mercifully scarce – but a more insidious strain: the slow-burn torment of trauma revisited. Exploring the house becomes a metaphor for exploring Samuel’s mind, his emotional history, his sorrow. “In order to escape,” the arch, omniscient narrator advises, “you have to go back, even if it hurts.” It’s a line that serves not only as mechanical instruction, but also psychological thesis. The game opens with a content warning about themes of bereavement, grief and abuse, and seldom steps out of their shadow.

The house – a beautifully rendered, nightmarish Spanish home – is a kind of domestic purgatory. Staircases twist back on themselves in impossible loops. Rooms rearrange their layouts between chapters. One moment you’re in a child’s bedroom, its walls papered with posters and shelves crowded with cuddly toys; the next, you’re descending into an industrial shaft under the floorboards that leads, impossibly, back to the bedroom. It’s as if Escher had sketched its blueprint on the back of a therapy intake form.

Luto parcels out its mystery carefully. The player learns, sometimes obliquely, that Samuel was a gifted child, fond of drawing, who once communicated with his father through yellow sticky notes left around the house. His mother taught him Spanish through homemade flashcards. He and his protective older brother, Isaac, were close; their shared adventures filled Samuel’s sketchbooks. It was, for a time, a happy household. But when Isaac falls ill, everything begins to unravel. There are no depictions of violence here – but as you puzzle together the pieces, you witness a slow collapse of innocence, replayed in dreamlike fragments, some tender, others unbearable.

The boy who once doodled cartoons grows into a young man with screenwriting ambitions. He cleaves to narrative as a form of order-making. It’s here that Luto gestures towards something more literary: the desire to build story out of pain, and the simultaneous terror that storytelling might fail us. The player presses forward not just to learn what happened, but to see if trauma can be mapped; if grief can be solved like a puzzle.

Like Myst or Riven – those lavish, solitary puzzle games of the 1990s – Luto is filled with cryptic symbols, locked doors and visual sleight of hand. You’re asked to notice the world changing when you’re not looking. Some puzzles are straightforward, others more metaphorical: one sequence requires you to walk through a series of doorways arranged to mimic the stages of grief, until the “right” emotional path is chosen.

By the end, Luto achieves something rare: a horror game that doesn’t merely deploy trauma as atmospheric texture, but engages with the mental architecture of suffering. It understands that the scariest place is not the basement, or the attic, but the unlit hallway of memory. You may not always find the clarity you seek, but if you can bear to turn and face the darkness, then perhaps the boxes in the hallway won’t stay half-packed. And maybe, finally, you can move on.

Luto, by Broken Bird Games, is available on PC, PS5, Xbox

Photograph by Broken Bird Games