Introduction

Hello! My name is Brandon Walsh, and I’m a 3D Environment Artist located in Vancouver. I’ve been creating art and playing video games my whole life. Originally, I wanted to become a concept artist since I love painting, and I’ve always been inspired by the games I played. I wasn’t sure back then how to join the game industry, so I pursued a visual arts degree. Eventually, I discovered that many concept artists were using 3D to speed up their workflow, so I began to teach myself Blender. After two years of studying, it became clear that I wasn’t going to gain the skills I needed to enter the game industry, so I decided to switch from my art degree to a diploma in 3D.

My digital art knowledge really took off when I enrolled at the British Columbia Institute of Technology in Burnaby (BCIT). When I was finally getting the lessons that I needed, I began to fall in love with 3D so much that I decided to pursue a career as a 3D artist. Once I earned my diploma, I began job hunting. I graduated from BCIT in 2022, and the industry was beginning to be hit hard. Despite the growing uncertainty of the industry, I kept practicing, networking, and applying. I love video games and this craft so much that nothing can stop me from pursuing this dream, no matter how long it takes.

After 2 years of job searching, I decided to enroll at Think Tank Training Centre in Vancouver. After seeing all the amazing work that came out of this school, I thought this could be a good place to enhance my portfolio and meet more like-minded people. Turns out I was right. I’ve learned so many valuable lessons and met amazing people.

Inspiration

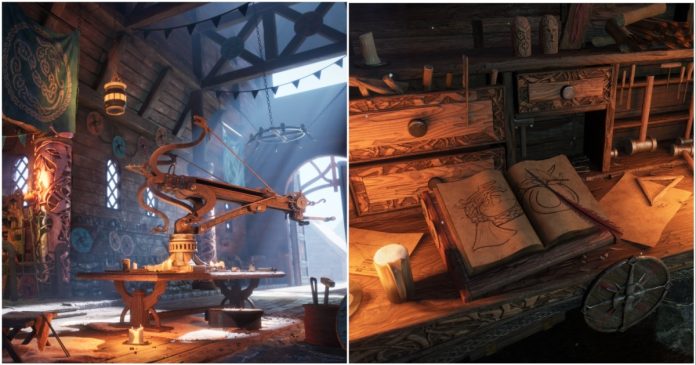

When I was searching through ArtStation, I came across this great concept called Viking’s Workshop, by Robert Galliers. When starting any project, it’s incredibly important to gather the right references. I built my reference board using PureRef and gathered images of Viking homes, furniture, weapons, materials, and screenshots from games for lighting and mood. I like to have it organized and color coordinated so that I can quickly home in on what I’m looking for.

When creating any environment, I like to learn about its history. I want to know about the culture, what materials people used, and how things were built. For example, it seems people in medieval Scandinavia primarily used oak and pine for building homes. When researching the ballista, I looked at Roman ballistae and how they functioned.

Robert Galliers

The concept’s architecture and decorations reminded me of God of War (2018) and How to Train Your Dragon, so I always had those titles in the back of my mind. I normally aim for a more realistic style, but this time I wanted to lean more towards a detail-rich and vibrant stylized look. Games like God of War, Ghost of Tsushima, and Horizon Zero Dawn have this mix of things being detailed and grounded in the real world, but with more exaggerated color and beauty. Almost like romanticism, where nature is portrayed as even grander and more expressive than it really is.

In these games that I mentioned, it feels like their worlds are shown in a high dynamic range, and the colors are somewhat overly saturated compared to what we typically see in real life. It’s a bit like XDR (extreme dynamic range) images of cities like Hong Kong or Las Vegas at night, with all the lights lit up. These are images of real places, but the boundaries of light and dark contrasts are pushed to the extreme, and it can create a dreamier effect.

Planning Composition

When establishing composition and blocking out my scenes, I like to go through these steps:

- Set up a camera in Maya to match the concept as closely as possible;

- Place primitive cubes and cylinders around with simple scaling and extrusions;

- Combine the blockout and import it into Unreal Engine;

- Do a quick lighting setup to get a feel for the lighting and mood.

For the rest of the week, I model as much as I can, starting with the big things and working my way down to the small assets. It is important to get the large architectural pieces in first because they take up most of the image. I’m essentially applying broad strokes like I would if I were painting on canvas.

Texturing Workflow

For this project, I went with a texel density of 512 pixels per meter, which proved to be flexible when I had to tile textures up or down. Once the large architectural pieces, like the walls and pillars, were in place, I created a first pass of materials using Substance 3D Designer. Since the scene consists mostly of wood, metal, and stone, I could focus a lot of my attention towards creating just a handful of good, tillable materials rather than uniquely texturing every asset.

Most of what I now know in 3D Designer was learned from Johnny Malcom’s lessons at Think Tank and his YouTube channel. The basic workflow I use for materials is just like how I create my environment pieces; we start with the large details and work our way down to the small high frequency details. For creating wood, it’s good to start with the grain since it’s the most obvious feature. All wood types have their own pattern, so I looked closely at oak to see how far apart, long, and wavy the grain is. I’ll start adding large gashes and cracks, then the smaller scratches. After the damages are finished, I can create the albedo and use a lot of the information I’ve created, like the grain and damages, to drive where I want different colors and dirt. For example, we can use a Flood Fill to randomize the color of the grain pattern and use the height information from the damages to add dirt and wear using Ambient Occlusion and Curvature.

Studying real-life references is the best way to achieve believable materials. Our brains will often lie to us despite seeing these details every day, so it is always important to have good reference images. Complex materials are often made up of many layers of subtle details rather than just a few layers of big, obvious details.

The stone wall took multiple attempts to find the right look. I experimented with building it purely in 3D Designer, modeling rocks to conform to the already existing material, physically stacking stones that I sculpted, and creating a tillable by baking it in 3D Designer. In the end, I decided to build a tileable material in 3D Designer, then I used the height information to create a displacement in ZBrush. I then decimated it to create my low-poly model. Since it already had UVs from the plane, I displaced all I had to do was clean up the edges so that it could tile, and I could repeat the stone wall as much as I liked. I used this technique so that I could have displaced geometry without the need for Nanite, just in case I ever work for a studio that doesn’t use Unreal Engine or Nanite. It also gives me a lot of control over the density of the mesh, and I can easily create LODs with decimation in ZBrush.

In this video, I speed through how I use displacement in ZBrush to create my stone wall.

For an environment with so much wood, the tiling material is doing most of the heavy lifting. Very few things in the scene are using high to low-poly baking. Most of the assets share the same tiling materials. The weapons required a little more unique detail, so they are using a combination of Substance 3D Designer and 3D Painter. Most of the baking was done in 3D Designer.

I made a graph that assigns 3 materials using color IDs that I applied when exporting out of Maya. When it was set up, all I had to do was bake the asset, then hook up the bakers to the graph node and rename each output before exporting. Each of these props receives a unique texture, but it’s a way to texture and bake a lot of similar assets quickly.

Some of them were taken into ZBrush for extra details on the high poly, but others are using the low poly to bake onto itself to get some ambient occlusion, curvature, etc. For things like the shields and sword, I wanted some unique details, so I brought them into Substance 3D Painter, applied the texture maps from Substance 3D Designer, and added the unique details, such as the designs on the shields. I drew each design in Photoshop and exported it as alphas:

For the fur hides, I used my tileable material with Parallax Occlusion and a Mesh Skirt (an opacity map on thin geometry around the edge of a mesh) for the loose hairs. I painted the mask in Substance 3D Painter by going in the direction of the hairs for better results.

The wooden walls were vertex-painted with 2 wood materials, a dirt material, and a random tint for each plank.

The planks were given different vertex colors before exporting out of Maya, which were then used to give the blue channel a different shade of blue on each plank. This helped to add more subtle variety in the color.

My method for retopology really depends on the assets I’m making. Not all environment assets require baking since we’re using a lot of tillable materials, so those can be optimized as they go. When UV unwrapping large assets, they can go outside of the 0-1 space so long as they maintain texel density. For props that require baking, sometimes I’ll create the high-poly first and then retopologize using the Quad Draw tool in Maya, especially if the asset was created in ZBrush. When you make the high-poly a live surface, you can draw your low-poly version over top of it.

Final Scene Assembly

Set dressing is one of my favorite parts of environment creation. Once all my assets are made and all the proxy assets have been replaced, I begin to duplicate things around while keeping an eye out for repetition that’s too noticeable. For tiny meshes, I like to use the Foliage Mode in Unreal to scatter the wood shavings and small stones.

I try to imagine myself as a character in this space and think about how I would make a mess of it. Maybe I would leave some tools around because I’m too tired to put them away, or I’m in the middle of working on the ballista. Perhaps I cleared the wood shavings off a section of the table, causing them to fall on the floor. When things are too neat and tidy, an environment can begin to feel artificial and lack that lived-in sort of feel. It is also easy to place things in a way that feels too deliberate, like it’s on display and less natural. This is something I’m always watching out for, and it takes practice. Looking around at how other people treat their environment and belongings really helps. A carpenter’s shop can appear messy, but all its tools have a place that is usually convenient and easy to access, if it’s too clean and organized, then it looks brand new. If something is placed somewhere that feels inconvenient, then it can appear confusing. It’s all about the sort of mood you want to establish.

Lighting & Rendering

Lighting is another part of environment creation that I really love because it can drastically affect the mood of a scene and bring more attention to areas of interest. If I have sunlight in my scene, then I like to use the Directional Light with Volumetric Fog to create light rays that point towards a place I want the viewer to look.

For areas where the candles and lamps are lit, I will either use a point light to spread the light in all directions or an area light to point the light towards something specific. It is important to know which lights are more expensive and to use as few as possible while achieving the look you want. A single point light can be used for multiple candles placed close together. I’m also observing how dark and soft the shadows are. I use the Post Process Volume to manually adjust the exposure to make sure my shadows aren’t too dark, and the highlights aren’t too bright. Modern lights are quite strong, so it is good for a medieval scene to look at how sunlight and fire affect shadows. Adding a little Bloom in the Post Process Volume can also lighten up shadows and give the light sources a soft glow to add some perceived realism.

Since I’m exaggerating the range of color in my scene, I gave my sunlight a blue tint to create a bigger contrast between the warm candlelight and the cold shadows. I created a Lookup Table (LUT) in Photoshop to push the range of color and add more vibrancy to the scene. I rendered a shot in Unreal, did some color correction in Photoshop, and exported a LUT, which I applied to the Post Process Volume. This was a great way to art-direct the color of my scene easily without drastically changing all the lights in Unreal.

I was rendering a shot every week, so my render settings were set up well early on. I follow William Faucher’s lighting and rendering videos as a starting point to get high-quality results. I highly recommend anyone who’s getting into rendering in Unreal to check out his stuff.

When rendering, it’s very important to give yourself enough time to render multiple times because there is nearly always something off or out of place that will appear. Even though my render settings were good throughout the project, I still had to make adjustments towards the end.

Conclusion

The entire project was created in about 14-16 weeks. The first week was choosing a concept, the second week was reference gathering, and the last 14 weeks were spent creating. The main challenge was creating a large library of assets without sacrificing quality and keeping the style consistent across the board. I learned how to push tiling materials even further while avoiding noticeable repetition. One of the biggest lessons was that I don’t need to make every single asset the most perfect prop in the world if it’s barely seen. It is much more effective to prioritize the most noticeable and important aspects of the scene when there’s a time limit.

Our goal as artists is to make everything to the best of our ability, but if no one is going to see the nails or boxes up close, then you don’t need to spend as much on them compared to the weapons and workbench. Make them look as amazing as you can, but don’t get so hung up on it that the project takes forever to finish. It is typical for artists to be perfectionists, but it is important to spend our time wisely and think about the big picture. Just like painting traditionally, I will often stand up and look at my screen from across the room or even look away for a moment to try and forget the scene so I can come back with fresh eyes. This helps to avoid getting tunnel vision.

If I were to give any advice to someone beginning their 3D journey, I’d say the most important thing is to have fun, create what you love, study the real world, never stop learning, and don’t keep comparing yourself to people with years or even decades of experience. Something else I’d recommend if you really want to improve fast is to be constantly seeking feedback and critiques. Don’t get offended when getting critiqued; it is easy to take it personally, but 90 percent of the time, it’s to help you improve on your craft. For nearly every art project I have critiqued, another person will spot something I was unaware of. Not all advice is good, which is why it’s important to get feedback from as many people as possible. Lastly, I want to mention that it has been a tough time in the industry, and my heart goes out to everyone who has been affected. To anyone like me who is seeking their first position or just beginning their 3D journey, don’t despair. Focus on the journey, keep creating art, and remind yourself why you’re pursuing this career. Why do I do this? Because I love it.