Jakub Szamalek landed a job at Polish developer CD Projekt Red in the strangest of circumstances. Halfway through his archeology PhD, he came to a realisation that he was already bored of academia and couldn’t face a career in the very subject he’d spent so long training for. Naturally, he started playing The Witcher 2.

It was only when faced with technical issues that he navigated to the CDPR website and noticed an advert for a game writer. He applied and the rest, as he says, is history. After spending time working on some of the biggest RPGs on the planet (and Gwent), he’s left the studio behind to forge his own path, founding new studio Rebel Wolves and writing a science-fiction thriller novel set aboard the International Space Station during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

We sat down with Szamalek to find out about Inner Space, The Blood of Dawnwalker, and the incredibly highs yet challenging lows of founding your own development studio.

From Witchers To Vampires

“I’m deeply convinced that there are ways in which you can tell emotional stories in video games that are told on a different level,” Szamalek explains to me over video call. He cites the scene where Geralt and his buddies are drinking in Kaer Morhen as one of his favourites that he helped write in The Witcher 3, alongside the opening in White Orchard.

“Video games are very well equipped at showing epic, nerve-wracking scenes of combat or exploration, but they’re having a harder time showing intimate and quieter moments in an equally engaging way,” he says. That’s why he poured so much of his effort into the intimate, platonic drinking scene in which Geralt reminisces with old friends. And that’s undoubtedly why the scene is revered among fans as an iconic piece of the game, integral to Geralt’s story and the wider narrative as a whole.

Games rarely include these all-important moments of downtime, but that’s what life is all about. How do you translate the experience of hanging out with your friends, Szamalek asks, while keeping the player engaged? It’s these deeply human experiences that he wants to focus on in his career moving forward.

“There’s room for more depth in video games,” he says. “And that’s something that I’m trying to find in the titles that I’m working on; to see how we can be real when telling stories in video games.”

That title he’s working on is The Blood of Dawnwalker, a vampiric RPG that he and studio Rebel Wolves have been working on for four years, since a cadre of developers left CD Projekt to forge their own path. While Szamalek maintains that his career at CDPR was “an awesome adventure, a rollercoaster” that he’s “deeply grateful” to have been a part of, he’s ready to slow down a bit and “work on something smaller, and have more control.”

While the trailer that premiered in the Xbox Showcase last month gave us a good sense of Blood of Dawnwalker’s style and, for want of a better word, vibe, Szamalek describes an interesting narrative tapestry that ensures no two playthroughs will be the same.

“We use the term narrative sandbox,” he explains. “So, instead of having several story arcs that you can either engage with or not, we created a story structure where you can go around the world and encounter different stories and weave them together into your own narrative.”

This is intended to give the player “maximum agency” and harks back to “the original premise of pen and paper RPGs and early cRPGs”. Blood of Dawnwalker won’t tell you what to do next, it’s down to you to figure out what threads you want to follow and how you’re going to tell your own story.

To The ISS, And Beyond

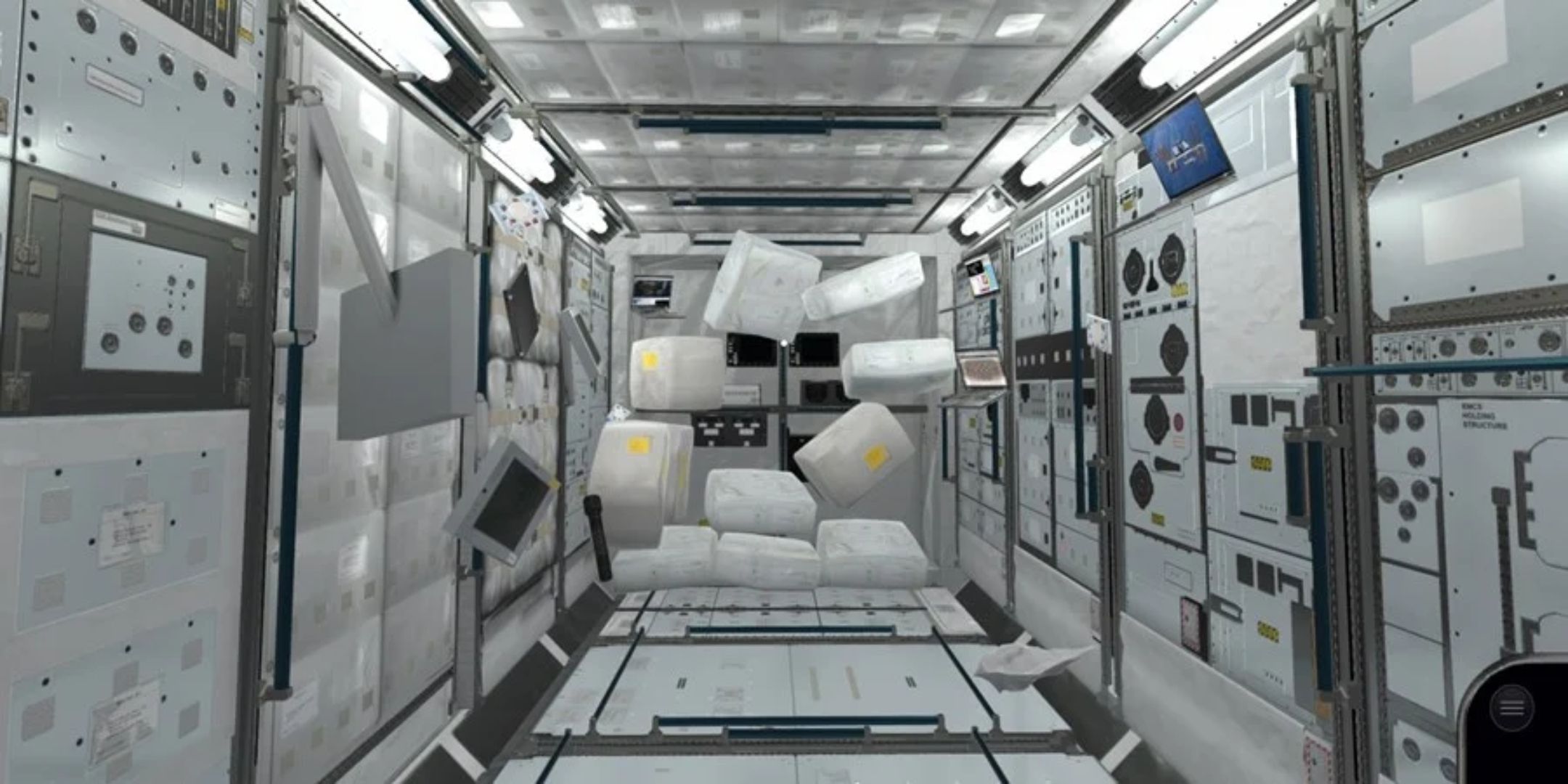

Alongside Szamalek’s writing for The Blood of Dawnwalker, he’s been penning a novel. Inner Space is a thriller set aboard the International Space Station. Suspicions of espionage rise between American and Russian astronauts as the latter’s government orders the invasion of Ukraine on the planet below. Tense and exciting, the novel is an exploration of the human psyche as much as it is the politics of the 2020s. But it all started because his daughter asked questions he didn’t know the answers to.

“I quickly realized that I know very little about everything that’s up above and that I lost that wonderful sense of wonder that kids have,” he explains. “They go out on a summer night, and they look up and they see the stars. Their jaws drop, and they’re like, ‘What’s all that and how do we fit into it.’ We [adults] fail to notice it any more […] It was a really beautiful adventure for me to try to understand all those things better so I could discuss them with my daughter and help her comprehend how we’re placed in the universe.”

On a trip to the Cité de l’Espace in Toulouse, France, Szamalek and his family entered a full-scale replica of the Russian space station, Mir. Szamalek isn’t a claustrophobic person, he tells me, but the cramped space with buttons and wires on every surface made him uncomfortable. It seems that this, as well as his research to answer his daughter’s questions, is where his novel was born.

As well as confronting questions of technology – vitally important to the author – and the cosmos, Szamalek is leaning hard into the geopolitical thriller in a sense that is reminiscent of classic locked-room mysteries of yore. You feel that same sense of claustrophobia that he felt aboard Mir, a sense that is exacerbated by escalating tensions between the American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts on board. The ISS becomes a microcosm of society, and Szamalek likens it to a divorced couple forced to cohabit while they pay off the remainder of the mortgage.

“The ISS is the product of a different era,” he says. “Where it felt like we could all come together for a greater cause, forget about our differences, and make things better – the Star Trek view of the universe.”

There are numerous differences between working on games and writing a book – most notably, the interactivity or lack thereof in each medium – but Szamalek was keen to explore less likeable characters and antiheroes in his novel, as he doesn’t believe there’s much space for them in games.

“The biggest challenge I found is that, in video games, you have to find your protagonist’s motivations and behaviors relatable,” he explains. “You have to be able to see yourself in the protagonist.”

On the other hand, books struggle to portray the element of choice, agency, of free will. “Choice is probably the most human thing there is,” Szamalek says. “You go through life and a lot of the time it may feel like you’re just going through the motions or following whatever current is taking you downstream right now. But there come moments where you realise that whatever you do or say now will affect your life moving forward. It’s a powerful feeling when you realise the road forks.

“Literature, try as it might, will never be able to convey that feeling, that moment, as well as games. Those moments where you’re facing these powerful choices are the moments where you truly feel alive and it can be scary. It can be fascinating.”

Szamalek clearly finds a balance between writing novels and video games, and stimulates different narrative muscles in each. He’s worked to find a balance while working what is effectively two jobs at once, and comes across as creatively fulfilled. Whatever risk was posed with leaving CD Projekt four years ago seems to have paid off. Inner Space offers a tense, linear tale of real-world politics and technology. The Blood of Dawnwalker trailer was well-received, and the storytelling ramifications of his open-ended narrative structure only excite me further.

If Szamalek can continue to balance all his projects with family life in Canada, his passion for storytelling promises treats in interactive and traditional fiction.

Inner Space is available from bookshops today, July 15, and The Blood of Dawnwalker is currently set for a 2026 release.