The video game industry was a very different place at the turn of the millennium. Everything was moving at such a fast and unpredictable pace, with technology advancing massively as each new generation reared its head. As players, we were consistently exposed to amazing new experiences that were equal parts groundbreaking and experimental, while developers were learning new techniques and means of creation as they went.

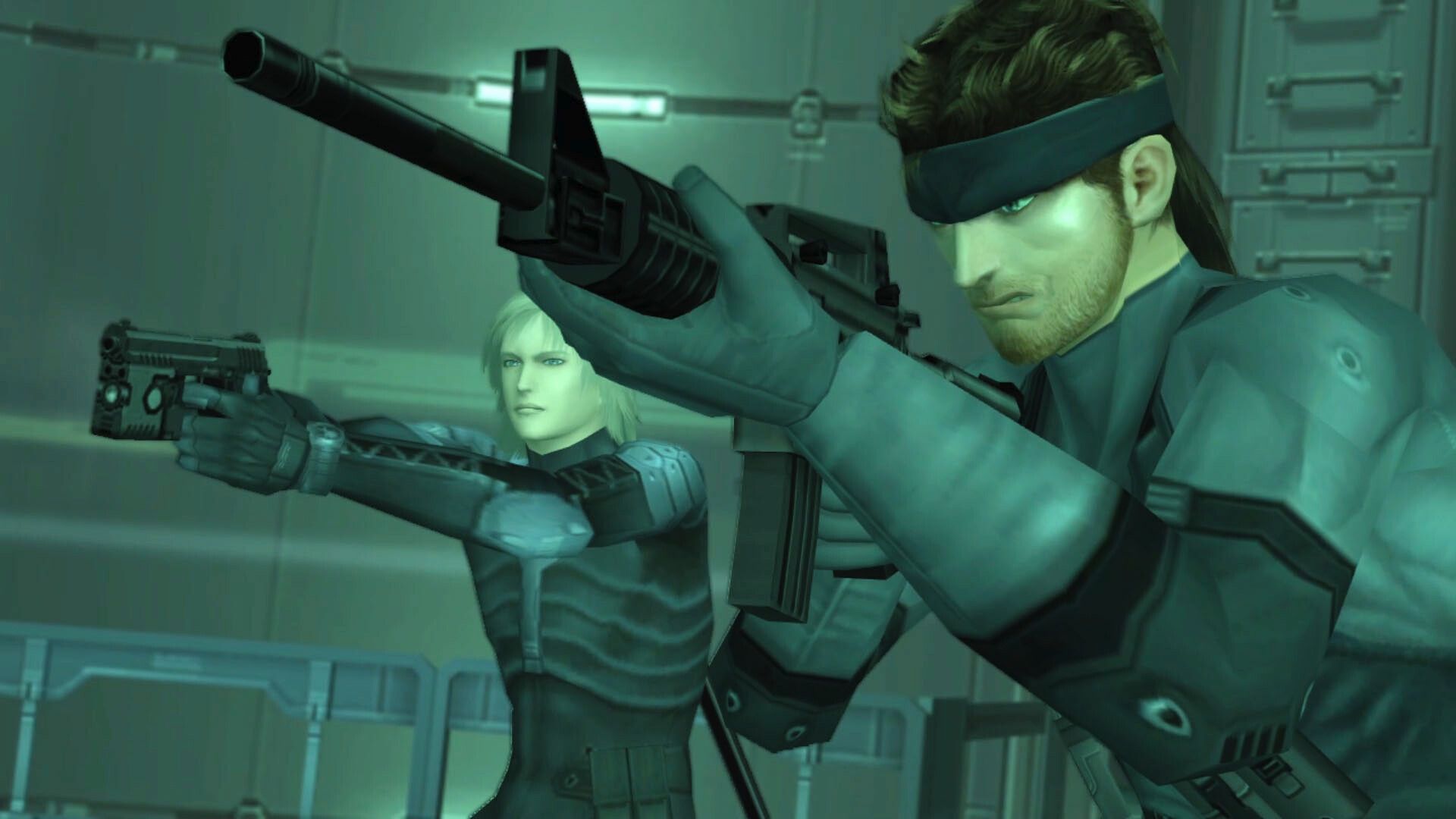

In hindsight, it was a time and place that can never be replicated no matter how hard we try, with the industry fully consumed by the whims of capitalism as major corporations aim to bleed every last dollar out of new releases. But in 1998, when Kojima Productions was in the trenches developing Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, the landscape could not have been more different. While Kojima and his team still had to abide by corporate whims, there seemed to be freedom to push boundaries that depressingly isn’t possible anymore.

But why has this time period suddenly sprung to mind, and why fixate on Metal Gear Solid 2 of all things when there are countless other classics to consider? Well, I recently spent time reading a translated version of Hideo Kojima’s personal diary spanning from the aftermath of Metal Gear Solid’s release in October 1998 to the days following Sons of Liberty’s arrival in December 2001. Most of the entries are brief, compiling a mix of personal and professional insights from a creative mind who was still finding his footing in the 3D world.

Before the release of Metal Gear Solid on the original PlayStation, Kojima cut his teeth on titles like Metal Gear 1&2, Snatcher, and Policenauts.

This diary provides an insight into the triple-A development process that, in modern times, is kept behind a veil of secrecy. But here, Kojima writes his diary with a surprisingly emotional honesty in which he doubts his abilities as a creative or expresses unexpected triumph when things go better than planned. It’s fascinating to watch him discover the improving hardware of the time and how he can utilise additional horsepower, better graphics, and more staff on his team to bring such a vision to life. But it’s also a journey defined by trepidation and fear, the encroaching paranoia that your plans aren’t going to come together until the last minute.

It begins with Kojima recounting his time at Sega’s ‘New Challenge Conference’, in which the DreamCast was shown off, offering a rough graphical and mechanical idea of Sons of Liberty and the form it would eventually take. Even at this early stage, though, Kojima ponders the limits of the PS2, and how far it could actually be pushed when depicting lifelike characters. Unusual to think about when the game would prove to be a groundbreaking yet polarising classic.

What I love most about this diary, though, is how it showcases Metal Gear Solid and Hideo Kojima in a state of growth, a caterpillar yet to burst from its chrysalis and take the form of a beautiful tactical espionage butterfly. Myriad entries have Kojima reflecting on awards earned by the original game or touching on pre-order figures for Sons of Liberty, all while falling into creative slumps and questioning whether he has what it takes. But when short bursts of creativity strike, you can see the simultaneous relief and excitement in his words.

Kojima makes an interesting point about new game developers during the creation of Metal Gear Solid and how most people didn’t get into this industry to “create something” but because video games were popular and profitable. But suddenly, the very same people are quick to paint themselves as such. Another way in which things have changed.

The same enthusiasm is transplanted onto the people he works with or his experience in directing motion capture performances for the first time. It’s strange to watch a developer who, in today’s world, has become a household name seem so normal and introspective.

It also speaks to how much better the industry has become at taking care of its talent, as on multiple occasions Kojima talks about being incredibly sick or needing to visit the doctor in the midst of development, yet he keeps on going so he doesn’t let people down. A rare swim at the local club isn’t going to keep your body ticking along, Kojima-san.

While I adore how this diary strips away the mystery of a defining moment in the medium’s history, I equally admire how it presents the everyday musings of Kojima’s life. He would often simply detail going to lunch with colleagues or discussing his ambitions for Metal Gear with other members of the industry that would go on to have similar legendary careers.

Despite working ridiculously long days, he still finds time to watch the latest films and shows, keeping on top of the popular culture he intends to pull from for his own creativity. I especially love how he reacts to pivotal media like The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Final Fantasy 8, or even The Matrix. The development team is entranced, often sneaking in sessions at the office before immediately inserting that enthusiasm into the game they’re creating. It was a period when both players and developers were learning so much all the time.

We also see Kojima reflect on global events, such as the bombing of Iraq by the US and UK in 1998 – codenamed Desert Fox – which, if the situation spiralled out of control, would upend the narrative plans for Metal Gear Solid 2. There were originally suspicions that a new Metal Gear was being developed in the country and would require US intervention. It wasn’t timely, and it’s saddening to see Kojima react with such despair at global affairs and how he is powerless to make a difference. Most notably, he states that, “The story of MGS can only exist in a world where peace prevails.”

Following the terrorist attacks in New York on September 11th, Kojima’s entry is brief and solemn – “At night, an incident occurred. It took many lives and shattered our dreams.”

There is beauty in the mundane nature of Kojima’s diary entries and how he tries to balance the stress of being a game director in an ever-growing industry with the desire to be someone who loves video games, film, and television, all while striving to remain informed on global affairs.

Over the course of three years, you watch as his perspective goes from one defined by stress and impossibility to pride and relief. Upon reading through the full diary, Kojma’s mindset on not just video games as an interactive medium, but how he can make stories which reflect our own world is clear to see. I’m not surprised he went on to create politically resonant work like the remaining Metal Gear Solid games and Death Stranding.

Related

Five Things Death Stranding 2 Doesn’t Tell You

There are a lot of mysteries in the world, but Death Stranding 2 doesn’t even begin to answer them.

Kojima would often neglect diary entries for entire months and weeks, leaving us to fill in the blanks of Metal Gear Solid 2’s development and what went on during that short period. And yet, no matter how short an entry might be or how pedestrian its content, it’s an intimate look into the creative process of making a masterpiece from a creator who never once realised the impact it would soon have. We don’t see things like this anymore, and that’s exactly why it’s worth treasuring.