UrbEx, the cool abbreviation for the mundane sounding hobby of urban exploration, is the act of exploring the abandoned places in our world. Think decaying nuclear reactors or unfinished skyscrapers. Daring hobbyists gain access to these spaces – often through less-than-legal means – and have a nose around. Many film their escapades, which allows wimps like me to enjoy their expeditions vicariously from my couch.

But I’ve never played a video game based on urban exploration. I’ve played a lot of things close, but never anything that quite scratches that UrbEx itch. This is a baffling oversight from game developers across the world, because exploring abandoned buildings shares core tenets with countless classic video game environments and mechanics.

Exploring, Urbanly

Nearly every video game forces you to explore. Whether it’s the open world of Mario Kart World or the side-scrolling ascent of Celeste, exploration is a core mechanic of all but the most abstract video games.

We praise games for hiding surprises in corners of castle crypts or creating a natural NPC sidequest that encourages you off the beaten path with a trail of delicious digital breadcrumbs. What’s more, games love sending us deep into abandoned places.

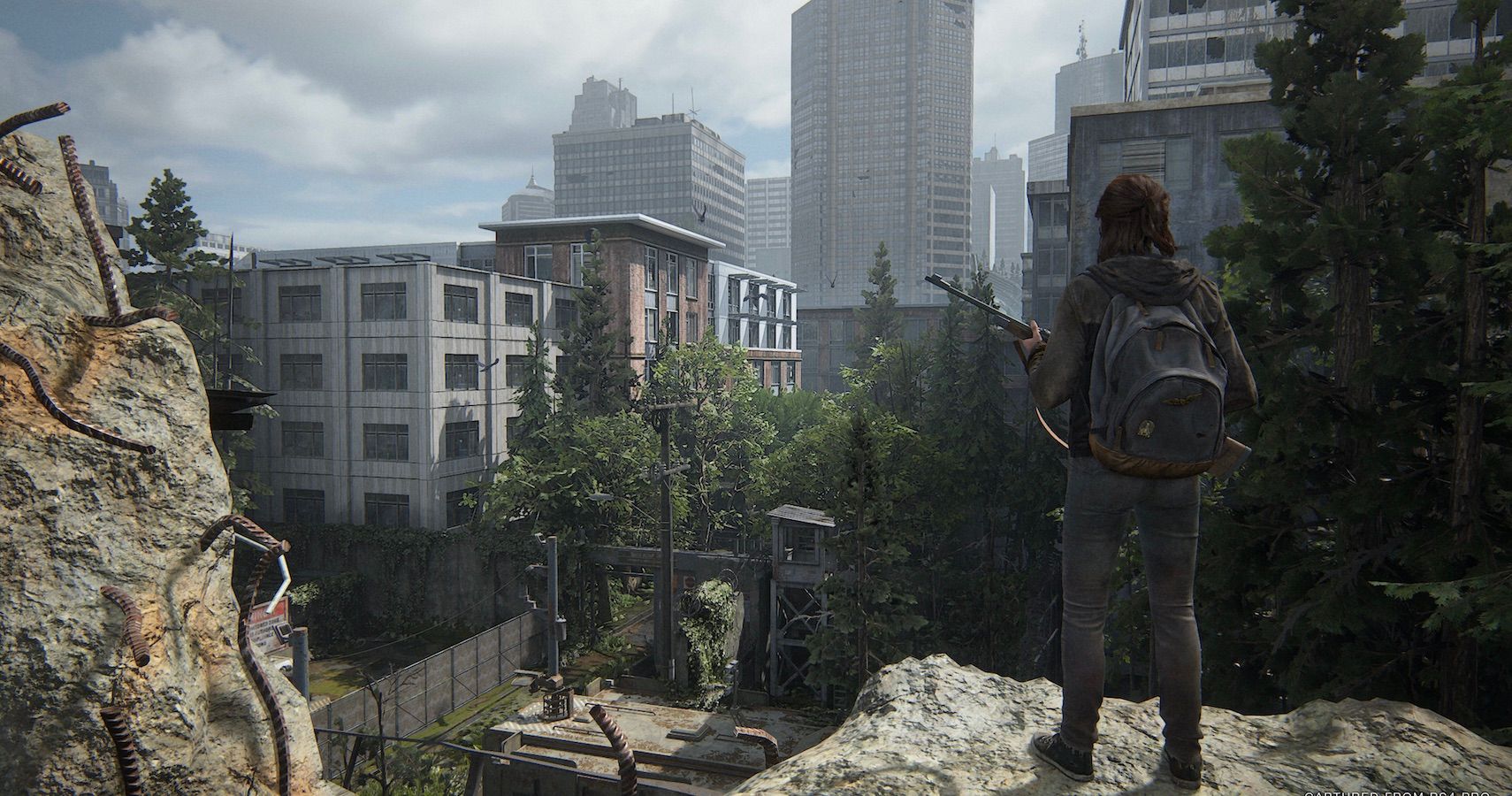

Hyrule Castle in Tears of the Kingdom. The town of Silent Hill. Seattle in The Last of Us Part 2. H*ck, any post-apocalyptic video game will be chock full of abandoned settlements for you to root around in. But none of it feels quite like UrbEx.

I’ve watched YouTubers like Shiey find old school books in Chernobyl, just like I’ve seen Ellie pick up a dusty guitar in The Last of Us. But the best urban explorations aren’t those into dangerous areas. They’re adventures into the mundane. When I watch someone break into a skyscraper that’s still under construction, it’s not to see the steel girders and half-fitted glass panels. It’s to see them ascend to the top floor and get a new perspective on the city they’re in. A city bustling with life as they’ve clambered through an eerie, empty space. It’s this juxtaposition that makes UrbEx so special, and that’s something that empty post-apocalyptic settings can’t ever hope to emulate.

Exploring, Mechanically

Leaving aside the environments themselves, the mechanics of UrbEx feel like they were pulled straight from a video game themselves. What’s more, the hobby is practically a pre-designed level.

First, you have a stealth section. Choose your entry point. Avoid the guards, dogs, workers, and anyone else who would apprehend you on your journey into the unknown.

After the stealth section comes platforming. This can be pretty basic in a modern, unfinished skyscraper (an early level), but could rise in difficulty to making vertigo-inducing jumps in a rusting nuclear reactor or rusting theme park.

This will also be when the majority of your exploring takes place. You can fill each level with branching paths, different routes through each building, and so much environmental storytelling you’d make Dead Space look half-hearted.

When you reach the top (or the bottom, depending on where you’re exploring), we can see the culmination of our efforts. A view of the city. A never-before-seen look at a secret bunker. Whatever it is, wherever you are, this is crucial for nailing the UrbEx experience. You need to make the level worth the player’s time. Perhaps this is where most games struggle.

It’s difficult to have such an impressive reveal in a video game. In a medium where we regularly travel to alien planets or visit the ancient past, how do you get players excited about seeing a regular city, from above? That’s the core question that anyone developing an UrbEx game must answer.

Exploring, Already

We’ve got our Urb, we’ve got our Ex. Now what? Some kind of story to knit it all together would be nice. This could take many forms, and I’ve got two examples of games that come pretty close to UrbEx to explain.

First up is Ghostwire: Tokyo, the creative director of which was Ikumi Nakamura, a keen urban explorer herself. Ghostwire: Tokyo’s story was one of its weaker points, though the Yokai hunting and exploring an abandoned Tokyo more than making up for it. But it followed the standard pattern for video game stories: cutscene, level, cutscene, boss, flashback, boss’ second phase, cutscene, etc. It was a little rote, but it served as an adequate vehicle to carry the more exciting gameplay loop.

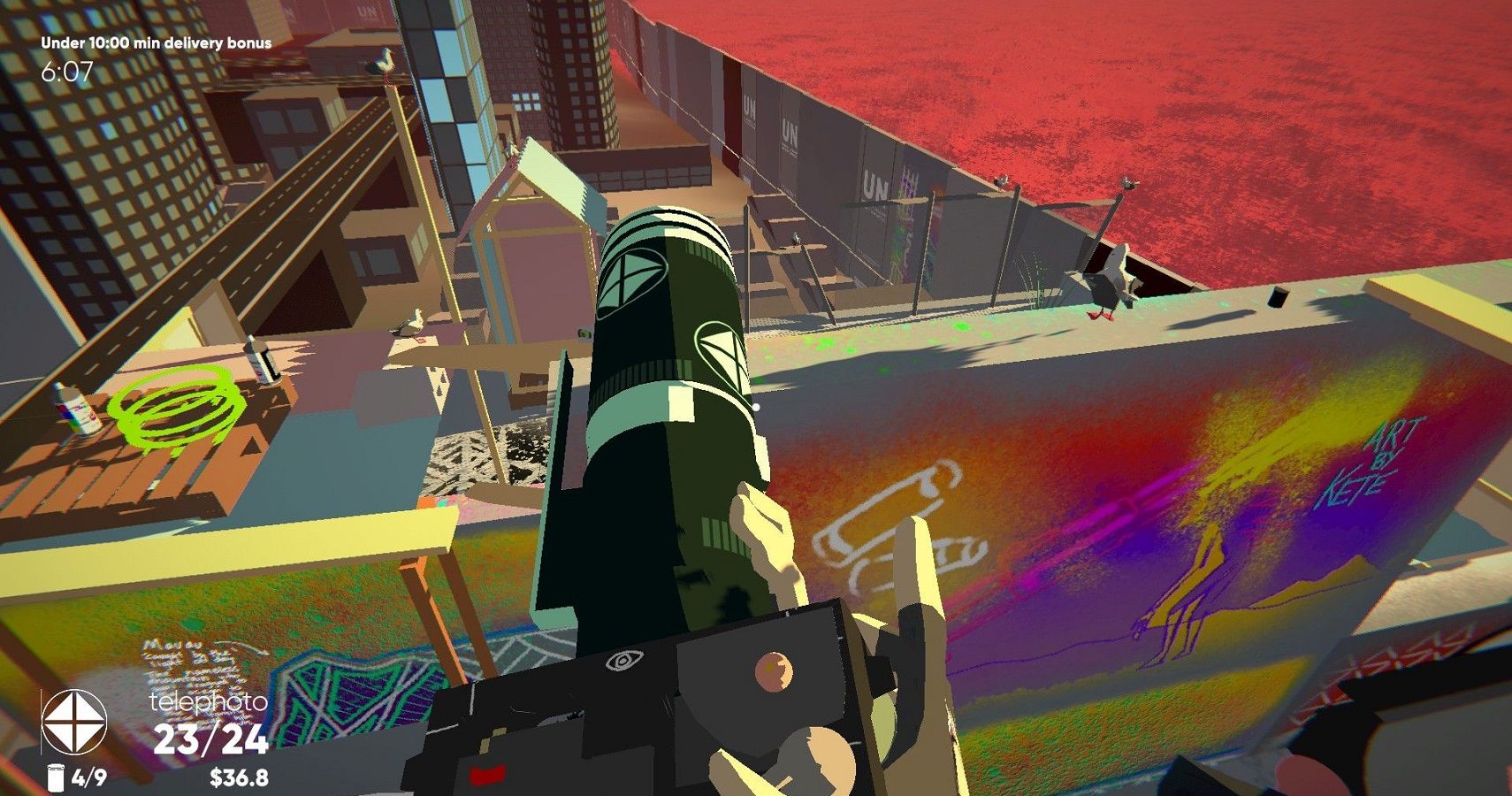

Umurangi Generation is the opposite of this. There are no cutscenes, there is no dialogue. Every story beat is told through the environments you photograph. Be it in the form of graffiti or warplanes flying overhead, you quickly learn that something’s not right in Aotearoa. I won’t spoil this excellent indie for you, but if someone made an alternate version of this with more exploring, I’d consider myself satisfied on my quest for a true UrbEx game.

There may be a great UrbEx game out there that I haven’t played. There are, quite literally, millions of video games in existence and I’m sorry to admit that I haven’t played them all. I hope that one of them embodies the experience I’m after. I hope that, somewhere out there, somebody has made a stealth-platformer with an engaging story that satisfies my craving for the juxtaposition of eerie quiet and bustling city life. If you’ve played that game – or if, indeed, you’ve made that game – please don’t hesitate to let me know. In the meantime, if someone could just make Ghostwire: Aotearoa, that’d be perfect.

Next

Forget The Open World, Mario Kart World’s Best Feature Is Its Futuristic Minimap

Mario Kart World’s free roam is absolutely transformed by its fantastic minimap.