It’s been 23 years since the first Battlefield game, and the video game industry is nearly unrecognizable to anyone who was immersed in it then. Many people who loved the games of that era have since become frustrated with where AAA (big budget) games have ended up.

Today, publisher EA is in full production on the next Battlefield title—but sources close to the project say it has faced culture clashes, ballooning budgets, and major disruptions that have left many team members fearful that parts of the game will not be finished to players’ satisfaction in time for launch during EA’s fiscal year.

They also say the company has made major structural and cultural changes to how Battlefield games are created to ensure it can release titles of unprecedented scope and scale. This is all to compete with incumbents like the Call of Duty games and Fortnite, even though no prior Battlefield has achieved anywhere close to that level of popular and commercial success.

I spoke with current and former EA employees who work or have recently worked directly on the game—they span multiple studios, disciplines, and seniority levels and all agreed to talk about the project on the condition of anonymity. Asked to address the reporting in this article, EA declined to comment.

According to these first-hand accounts, the changes have led to extraordinary stress and long hours. Every employee I spoke to across several studios either took exhaustion leave themselves or directly knew staffers who did. Two people who had worked on other AAA projects within EA or elsewhere in the industry said this project had more people burning out and needing to take leave than they’d ever seen before.

Each of the sources I spoke with shared sincere hopes that the game will still be a hit with players, pointing to its strong conceptual start and the talent, passion, and pedigree of its development team. Whatever the end result, the inside story of the game’s development illuminates why the medium and the industry are in the state they’re in today.

Table of Contents

The road to Glacier

To understand exactly what’s going on with the next Battlefield title—codenamed Glacier—we need to rewind a bit.

In the early 2010s, Battlefield 3 and Battlefield 4 expanded the franchise audience to more directly compete with Call of Duty, the heavy-hitter at the time. Developed primarily by EA-owned, Sweden-based studio DICE, the Battlefield games mixed the franchise’s promise of combined arms warfare and high player counts with Call of Duty’s faster pace and greater platform accessibility.

This was a golden age for Battlefield. However, 2018’s Battlefield V launched to a mixed reception, and EA began losing players’ attention in an expanding industry.

Battlefield 3, pictured here, kicked off the franchise’s golden age. Credit: EA

Instead, the hot new online shooters were Overwatch (2016), Fortnite (2017), and a resurgent Call of Duty. Fortnite was driven by a popular new gameplay mode called Battle Royale, and while EA attempted a Battle Royale mode in Battlefield V, it didn’t achieve the desired level of popularity.

After V, DICE worked on a Battlefield title that was positioned as a throwback to the glory days of 3 and 4. That game would be called Battlefield 2042 (after the future year in which it was set), and it would launch in 2021.

The launch of Battlefield 2042 is where Glacier’s development story begins. Simply put, the game was not fun enough, and Battlefield 2042 launched as a dud.

Don’t repeat past mistakes

Players were disappointed—but so were those who worked on 2042. Sources tell me that prior to launch, Battlefield 2042 “massively missed” its alpha target—a milestone by which most or all of the foundational features of the game are meant to be in place. Because of this, the game’s final release would need to be delayed in order to deliver on the developers’ intent (and on players’ expectations).

“Realistically, they have to delay the game by at least six months to complete it. Now, they eventually only delayed it by, I think, four or five weeks, which from a development point of view means very little,” said one person who worked closely with the project at the time.

Developers at DICE had hoped for more time. Morale fell, but the team marched ahead to the game’s lukewarm launch.

Ultimately, EA made back some ground with what the company calls “live operations”—additional content and updates in the months following launch—but the game never fulfilled its ambitions.

Plans were already underway for the next Battlefield game, so a postmortem was performed on 2042. It concluded that the problems had been in execution, not vision. New processes were put into place so that issues could be identified earlier and milestones like the alpha wouldn’t be missed.

To help achieve this, EA hired three industry luminaries to lead Glacier, all of them based in the United States.

The franchise leadership dream team

2021 saw EA bring on Byron Beede as general manager for Battlefield; he had previously been general manager for both Call of Duty (including the Warzone Battle Royale) and the influential shooter Destiny. EA also hired Marcus Lehto—co-creator of Halo—as creative chief of a newly formed Seattle studio called Ridgeline Games, which would lead the development of Glacier’s single-player campaign.

Finally, there was Vince Zampella, one of the leaders of the team that initially created Call of Duty in 2003. He joined EA in 2010 to work on other franchises, but in 2021, EA announced that Zampella would oversee Battlefield moving forward.

In the wake of these changes, some prominent members of DICE departed, including General Manager Oskar Gabrielson and Creative Director Lars Gustavsson, who had been known by the nickname “Mr. Battlefield.” With this changing of the guard, EA was ready to place a bigger bet than ever on the next Battlefield title.

100 million players

While 2042 struggled, competitors Call of Duty and Fortnite were posting astonishing player and revenue numbers, thanks in large part to the popularity of their Battle Royale modes.

EA’s executive leadership believed Battlefield had the potential to stand toe-to-toe with them, if the right calls were made and enough was invested.

A lofty player target was set for Glacier: 100 million players over a set period of time that included post-launch.

Fortnite‘s huge success has publishers like EA chasing the same dollars. Credit: Epic Games

“Obviously, Battlefield has never achieved those numbers before,” one EA employee told me. “It’s important to understand that over about that same period, 2042 has only gotten 22 million,” another said. Even 2016’s Battlefield 1—the most successful game in the franchise by numbers—had achieved “maybe 30 million plus.”

Of course, most previous Battlefield titles had been premium releases, with an up-front purchase cost and no free-to-play mode, whereas successful competitors like Fortnite and Call of Duty made their Battle Royale modes freely available, monetizing users with in-game purchases and season passes that unlocked post-launch content.

It was thought that if Glacier did the same, it could achieve comparable numbers, so a free-to-play Battle Royale mode was made a core offering for the title, alongside a six-hour single-player campaign, traditional Battlefield multiplayer modes like Conquest and Rush, a new free-to-play mode called Gauntlet, and a community content mode called Portal.

The most expensive Battlefield ever

All this meant that Glacier would have a broader scope than its predecessors. Developers say it has the largest budget of any Battlefield title to date.

The project targeted a budget of more than $400 million back in early 2023, which was already more than was originally planned at the start.

However, major setbacks significantly disrupted production (more on that in a moment) and hundreds of additional developers were brought onto Glacier from various EA-owned studios to get things back on track, significantly increasing the cost. Multiple team members with knowledge of the project’s finances told me that the current projections are now well north of that $400 million amount.

Skepticism in the ranks

Despite the big ambitions of the new leadership team and EA executives, “very few people” working in the studios believed the 100 million target was achievable, sources told me. Many of those who had worked on Battlefield for a long time at DICE in Stockholm were particularly skeptical.

“Among the things that we are predicting is that we won’t have to cannibalize anyone else’s sales,” one developer said. “That there’s just such an appetite out there for shooters of this kind that we will just naturally be able to get the audience that we need.”

Regarding the lofty player and revenue targets, one source said that “nothing in the market research or our quality deliverables indicates that we would be anywhere near that.”

“I think people are surprised that they actually worked on a next Battlefield game and then increased the ambitions to what they are right now,” said another.

In 2023, a significant disruption to the project put one game mode in jeopardy, foreshadowing a more troubled development than anyone initially imagined.

Ridgeline implodes

Battlefield games have a reputation for middling single-player campaigns, and Battlefield 2042 didn’t include one at all. But part of this big bet on Glacier was the idea of offering the complete package, so Ridgeline Games scaled up while working on a campaign EA hoped would keep Battlefield competitive with Call of Duty, which usually has included a single-player campaign in its releases.

The studio worked on the campaign for about two years while it was also scaling and hiring talent to catch up to established studios within the Battlefield family.

It didn’t work out. In February 2024, Ridgeline was shuttered, Halo luminary Marcus Lehto left the company, and the rest of the studios were left to pick up the pieces. When a certain review came up not long before the studio was shuttered, Glacier’s top leadership were dissatisfied with the progress they were seeing, and the call was made.

Sources in EA teams outside Ridgeline told me that there weren’t proper check-ins and internal reviews on the progress, obscuring the true state of the project until the fateful review.

On the other hand, those closer to Ridgeline described a situation in which the team couldn’t possibly complete its objectives, as it was expected to hire and scale up from zero while also meeting the same milestones as established studios with resources already in place. “They kept reallocating funds—essentially staff months—out of our budget,” one person told me. “And, you know, we’re sitting there trying to adapt to doing more with less.”

A marketing image from EA showing now-defunct Ridgeline Games on the list of groups involved. Credit: EA

After the shuttering of Ridgeline, ownership of single-player shifted to three other EA studios: Criterion, DICE, and Motive. But those teams had a difficult road ahead, as “there was essentially nothing left that Ridgeline had spent two years working on that they could pick up on and build, so they had to redo essentially everything from scratch within the same constraints of when the game had to release.”

Single-player was two years behind. As of late spring 2025, it was the only game mode that had failed to reach alpha, well over a year after the initial overall alpha target for the project.

Multiple sources said its implosion was symptomatic of some broader cultural and process problems that affected the rest of the project, too.

Culture shock

Speaking with people who have worked or currently work at DICE in Sweden, the tension between some at that studio and the new, US-based leadership team was obvious—and to a degree, that’s expected.

DICE had “the pride of having started Battlefield and owned that IP,” but now the studio was just “supporting it for American leadership,” said one person who worked there. Further, “there’s a lot of distrust and disbelief… when it comes to just operating toward numbers that very few people believe in apart from the leadership.”

But the tensions appear to go deeper than that. Two other major factors were at play: scaling pains as the scope of the project expanded and differences in cultural values between US leadership and the workers in Europe.

“DICE being originally a Swedish studio, they are a bit more humble. They want to build the best game, and they want to achieve the greatest in terms of the game experience,” one developer told me. “Of course, when you’re operated by EA, you have to set financial expectations in order to be as profitable as possible.”

That tension wasn’t new. But before 2042 failed to meet expectations, DICE Stockholm employees say they were given more leeway to set the vision for the game, as well as greater influence on timeline and targets.

Some EU-based team members were vocally dismayed at how top-down directives from far-flung offices, along with the US company’s emphasis on quarterly profits, have affected Glacier’s development far more than with previous Battlefield titles.

This came up less in talking to US-based staff, but everyone I spoke with on both continents agreed on one thing: Growing pains accompanied the transition from a production environment where one studio leads and others offer support to a new setup with four primary studios—plus outside support from all over EA—and all of it helmed by LA-based leadership.

EA is not alone in adopting this approach; it’s also used by competitor Activision-Blizzard on the Call of Duty franchise (though it’s worth noting that a big hit like Epic Games’ Fortnite has a very different structure).

Whereas publishers like EA and Activision-Blizzard used to house several studios, each of which worked on its own AAA game, they now increasingly make bigger bets on singular games-as-a-service offerings, with several of their studios working in tandem on a single project.

“Development of games has changed so much in the last 10 to 15 years,” said one developer. The new arrangement excites investors and shareholders, who can imagine returns from the next big unicorn release, but it can be a less creatively fulfilling way to work, as directives come from the top down, and much time is spent on dealing with inter-studio process. Further, it amplifies the effects of failures, with a higher human cost to people working on projects that don’t meet expectations.

It has also made the problems that affected Battlefield 2042‘s development more difficult to avoid.

Clearing the gates

EA studios use a system of “gates” to set the pace of development. Projects have to meet certain criteria to pass each gate.

For gate one, teams must have a clear sense of what they want to make and some proof of concept showing that this vision is achievable.

As they approach gate two, they’re building out and testing key technology, asking themselves if it can work at scale.

Gate three signifies full production. Glacier was expected to pass gate three in early 2023, but it was significantly delayed. When it did pass, some on the ground questioned whether it should have.

“I did not see robust budget, staff plan, feature list, risk planning, et cetera, as we left gate three,” said one person. In the way EA usually works, these things would all be expected at this stage.

As the project approached gate three and then alpha, several people within the organization tried to communicate that the game wasn’t on footing as firm as the top-level planning suggested. One person attributed this to the lack of a single source of truth within the organization. While developers tracked issues and progress in one tool, others (including project leadership) leaned on other sources of information that weren’t as tied to on-the-ground reality when making decisions.

A former employee with direct knowledge of production plans told me that as gate three approached, prototypes of some important game features were not ready, but since there wasn’t time to complete proofs of concept, the decision was handed down to move ahead to production even though the normal prerequisites were not met.

“If you don’t have those things fleshed out when you’re leaving pre-pro[duction], you’re just going to be playing catch-up the entire time you’re in production,” this source said.

In some cases, employees who flagged the problems believed they were being punished. Two EA employees each told me they found themselves cut out of meetings once they raised concerns like this.

Gate three was ultimately declared clear, and as of late May 2025, alpha was achieved for everything except the single-player campaign. But I’m told that this occurred with some tasks still unestimated and many discrepancies remaining, leaving the door open to problems and compromises down the road.

The consequences for players

Because of these issues, the majority of the people I spoke with said they expect planned features or content to be cut before the game actually launches—which is normal, to a degree. But these common game development problems can contribute to other aspects of modern AAA gaming that many consumers find frustrating.

First off, making major decisions so late in the process can lead to huge day-one patches. Players of all types of AAA games often take to Reddit and social media to malign day-one patches as a frustrating annoyance for modern titles.

Battlefield 2042 had a sizable day-one patch. When multiplayer RPG Anthem (another big investment by EA) launched to negative reviews, that was partly because critics and others with pre-launch access were playing a build that was weeks old; a day-one patch significantly improved some aspects of the game, but that came after the negative press began to pour out.

Anthem, another EA project with a difficult development, launched with a substantial day-one patch. Credit: EA

Glacier’s late arrival to Alpha and the teams’ problems with estimating the status of features could lead to a similarly significant day-one patch. That’s in part because EA has to deliver the work to external partners far in advance of the actual launch date.

“They have these external deadlines to do with the submissions into what EA calls ‘first-party’—that’s your PlayStation and Xbox submissions,” one person explained. “They have to at least have builds ready that they can submit.”

What ends up on the disc or what pre-loads from online marketplaces must be finalized long before the game’s actual release date. When a project is far behind or prone to surprises in the final stretch, those last few weeks are where a lot of vital work happens, so big launch patches become a necessity.

These struggles over content often lead to another pet peeve of players: planned launch content being held until later. “There’s a bit of project management within the Battlefield project that they can modify,” a former senior EA employee who worked on the project explained. “They might push it into Season 1 or Season 2.”

That way, players ultimately get the intended feature or content, but in some cases, they may end up paying more for it, as it ends up being part of a post-launch package like a battle pass.

These challenges are a natural extension of the fiscal-quarter-oriented planning that large publishers like EA adhere to. “The final timelines don’t change. The final numbers don’t change,” said one source. “So there is an enormous amount of pressure.”

A campaign conundrum

Single-player is also a problem. “Single-player in itself is massively late—it’s the latest part of the game,” I was told. “Without an enormous patch on day one or early access to the game, it’s unrealistic that they’re going to be able to release it to what they needed it to do.”

If the single-player mode is a linear, narrative campaign as originally planned, it may not be possible to delay missions or other content from the campaign to post-launch seasons.

“Single-player is secondary to multiplayer, so they will shift the priority to make sure that single-player meets some minimal expectations, however you want to measure that. But the multiplayer is the main focus,” an EA employee said.

“They might have to cut a part of the single-player out in order for the game to release with a single-player [campaign] on it,” they continued. “Or they would have to severely work through the summer and into the later part of this year and try to fix that.”

That—and the potential for a disappointing product—is a cost for players, but there are costs for the developers who work on the game, too.

Because timelines must be kept, and not everything can be cut or moved post-launch, it falls on employees to make up the gap. As we’ve seen in countless similar reports about AAA video game development before, that sometimes means longer hours and heavier stress.

AAA’s burnout problem

More than two decades ago, the spouse of an EA employee famously wrote an open letter to bring attention to the long hours and high stress that developers at the company faced.

Since then, some things have improved. People at all levels within EA are more conscious of the problems that were highlighted, and there have been efforts to mitigate some of them, like more comp time and mental health resources. However, many of those old problems linger in some form.

I heard several first-hand accounts of people working on Glacier who had to take stress or mental or exhaustion health leave, ranging from a couple of weeks to several months.

“There’s like—I would hesitate to count—but a large number compared to other projects I’ve been on who have taken mental exhaustion leave here. Some as short as two weeks to a month, some as long as eight months and nine,” one staffer told me after saying they had taken some time themselves.

This was partly because of long hours that were required when working directly with studios in both the US and Europe—a symptom of the new, multi-studio structure.

“My day could start as early as 5 [am],” one person said. The first half of the day involved meetings with a studio in one part of the world while the second included meetings with a studio in another region. “Then my evenings would be spent doing my work because I’d be tied up juggling things all across the board and across time zones.”

This sort of workload was not limited to a brief, planned period of focused work, the employees said. Long hours were particularly an issue for those working in or closely with Ridgeline, the studio initially tasked with making the game’s single-player campaign.

From the beginning, members of the Ridgeline team felt they were expected to deliver work at a similar level to that of established studios like DICE or Ripple Effect before they were even fully staffed.

“They’ve done it before,” one person who was involved with Ridgeline said of DICE. “They’re a well-oiled machine.” But Ridgeline was “starting from zero” and was “expected to produce the same stuff.”

Within just six months of the starting line, some developers at Ridgeline said they were already feeling burned out.

In the wake of the EA Spouses event, EA developed resources for employees. But in at least some cases, they weren’t much help.

“I sought some, I guess, mental help inside of EA. From HR or within that organization of some sort, just to be able to express it—the difficulties that I experienced personally or from coworkers on the development team that had experienced this, you know, that had lived through that,” said another employee. “And the nature of that is there’s nobody to listen. They pretend to listen, but nobody ultimately listens. Very few changes are made on the back of it.”

This person went on to say that “many people” had sought similar help and felt the same way, as far back as the post-launch period for 2042 and as recently as a few months ago.

Finding solutions

There have been a lot of stories like this about the games industry over the years, and it can feel relentlessly grim to keep reading them—especially when they’re coming alongside frequent news of layoffs, including at EA. Problems are exposed, but solutions don’t get as much attention.

In that spirit, let’s wrap up by listening to what some in the industry have said about what doing things better could look like—with the admitted caveat that these proposals are still not always common practice in AAA development.

“Build more slowly”

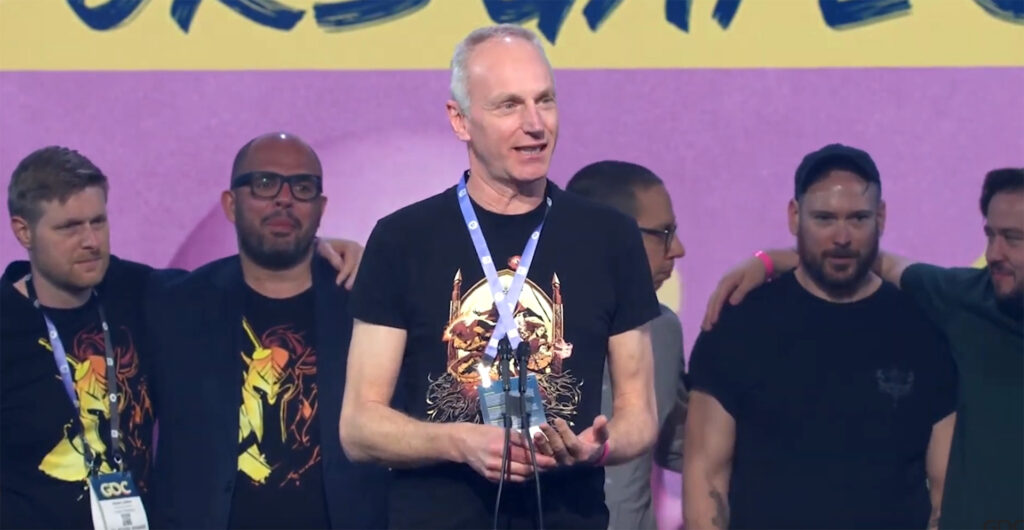

When Swen Vincke—studio head for Larian Studios and game director for the runaway success Baldur’s Gate 3—accepted an award at the Game Developers Conference, he took his moment on stage to express frustration at publishers like EA.

“I’ve been fighting publishers my entire life, and I keep on seeing the same, same, same mistakes over and over and over,” he said. “It’s always the quarterly profits. The only thing that matters are the numbers.”

After the awards show, he took to X to clarify his statements, saying, “This message was for those who try to double their revenue year after year. You don’t have to do that. Build more slowly and make your aim improving the state of the art, not squeezing out the last drop.”

Swen Vincke giving a speech at the 2024 Game Developers Choice Awards. Credit: Game Developers Conference

In planning projects like Glacier, publicly traded companies often pursue huge wins—and there’s even more pressure to do so if a competing company has already achieved big success with similar titles.

But going bigger isn’t always the answer, and many in the industry believe the “one big game” strategy is increasingly nonviable.

In this attention economy?

There may not be enough player time or attention to go around, given the numerous games-as-a-service titles that are as large in scope as Call of Duty games or Fortnite. Despite the recent success of new entrant Marvel Rivals, there have been more big AAA live service shooter flops than wins in recent years.

Just last week, a data-based report by prominent games marketing newsletter GameDiscoverCo came to a prescient realization. “Genres like Arena Shooter, Battle Royale, and Hero Shooter look amazing from a revenue perspective. But there’s only 29 games in all of Steam’s history that have grossed >$1m in those subgenres,” wrote GameDiscoverCo’s Simon Carless.

It gets worse. “Only Naraka Bladepoint, Overwatch 2 & Marvel Rivals have grossed >$25m and launched since 2020 in those subgenres,” Carless added. (It’s important to clarify that he is just talking Steam numbers here, though.) That’s a stark counterpoint to reports that Call of Duty has earned more than $30 billion in lifetime revenue.

Employees of game publishers and studios are deeply concerned about this. In a 2025 survey of professional game developers, “one of the biggest issues mentioned was market oversaturation, with many developers noting how tough it is to break through and build a sustainable player base.”

Despite those headwinds, publishers like EA are making big bets in well-established spaces rather than placing a variety of smaller bets in newer areas ripe for development. Some of the biggest recent multiplayer hits on Steam have come from smaller studios that used creative ideas, fresh genres, strong execution, and the luck (or foresight) of reaching the market at exactly the right time.

That might suggest that throwing huge teams and large budgets up against well-fortified competitors is an especially risky strategy—hence some of the anxiety from the EA developers I spoke with.

Working smarter, not harder

That anxiety has led to steadily growing unionization efforts across the industry. From QA workers at Bethesda to more wide-ranging unions at Blizzard and CD Projekt Red, there’s been more movement on this front in the past two or three years than there had been in decades beforehand.

Unionization isn’t a cure-all, and it comes with its own set of new challenges—but it does have the potential to shift some of the conversations toward more sustainable practices, so that’s another potential part of the solution.

Insomniac Games CEO Ted Price spoke authoritatively on sustainability and better work practices for the industry at 2021’s Develop:Brighton conference:

I think the default is to brute force the problem—in other words, to throw money or people at it, but that can actually cause more chaos and affect well-being, which goes against that balance. The harder and, in my opinion, more effective solution is to be more creative within constraints… In the stress of hectic production, we often feel we can’t take our foot off the gas pedal—but that’s often what it takes.

That means publishers and studios should plan for problems and work from accurate data about where the team is at, but it also means having a willingness to give their people more time, provided the capital is available to do so.

Giving people what they need to do their jobs sounds like a simple solution to a complex problem, but it was at the heart of every conversation I had about Glacier.

Most EA developers—including leaders who are beholden to lofty targets—want to make a great game. “At the end of the day, they’re all really good people and they work really hard and they really want to deliver a good product for their customer,” one former EA developer assured me as we ended our call.

As for making the necessary shifts toward sustainability in the industry, “It’s kind of in the best interest of making the best possible game for gamers,” explained another. “I hope to God that they still achieve what they need to achieve within the timelines that they have, for the sake of Battlefield as a game to actually meet the expectations of the gamers and for people to maintain their jobs.”

Samuel Axon is the editorial lead for tech and gaming coverage at Ars Technica. He covers AI, software development, gaming, entertainment, and mixed reality. He has been writing about gaming and technology for nearly two decades at Engadget, PC World, Mashable, Vice, Polygon, Wired, and others. He previously ran a marketing and PR agency in the gaming industry, led editorial for the TV network CBS, and worked on social media marketing strategy for Samsung Mobile at the creative agency SPCSHP. He also is an independent software and game developer for iOS, Windows, and other platforms, and he is a graduate of DePaul University, where he studied interactive media and software development.